Image credit: Unsplash

Educators in New York City schools are preparing students for upcoming state reading tests through ramped-up efforts dubbed as “sprints.” Educators can arrange for further reading practice for students before and after class throughout the week, on Saturdays, or during students’ spring break from March 10th through April 22nd. Improving literacy rates has been top of mind for educators, district officials, and politicians alike, and proponents of the measure contend these sprints are key to these needed improvements. While district officials have welcomed the measure, some educators and experts have questioned the value and efficacy of the sprint.

A Preparatory Sprint

District officials have directed school leadership to begin a period of additional focused test preparation for students in grades 3-5 who are nearing the proficiency threshold on state reading exams. Per the district’s instructions, these students are to receive an additional 30-50 minutes of designated reading practice weekly. The students identified for extra reading practice are estimated to be approximately 67,000 based on the results of mid-year exams, or approximately 38% of the students in grades 3-5.

Messaging obtained from the NYC superintendent’s office indicates that with “collective focus and intentionality, we are poised to achieve up to a 5% increase in ELA proficiency this spring.” The superintendent is further lauding the measure, encouraging school principals to collaborate with the district’s direction to “make this Spring a success and ensure that our students enter the ELA assessment period fully prepared and confident!”

Some Concerns and Support for the Sprint

Response to the measure has been varied. With some schools, the “sprints” are quite similar to what campuses already do to prepare for exams. Principal Lorenzo Chambers remarks that his “school is already doing it so it’s not shocking or anything different,” further commenting on the flexibility of the program and the ease of implementation. At his own school, like others, Chambers has broadened the effort to include increased instruction in math as well, targeting students through grade 8.

Still, some critics are concerned with the possible pitfalls of such a program. Teachers College professor Aaron Pallas notes that as the measure focuses on students who are within striking distance of proficiency, students with the lowest scores are left behind. Suggesting that increasing literacy rates is a marathon rather than a sprint, he questions why targeted instruction doesn’t occur throughout the year. Some principals agree with Pallas, expressing their concerns anonymously that the sprint may leave struggling students without needed support. Others argue that the short timeline for implementing the test prep measures will limit its effectiveness.

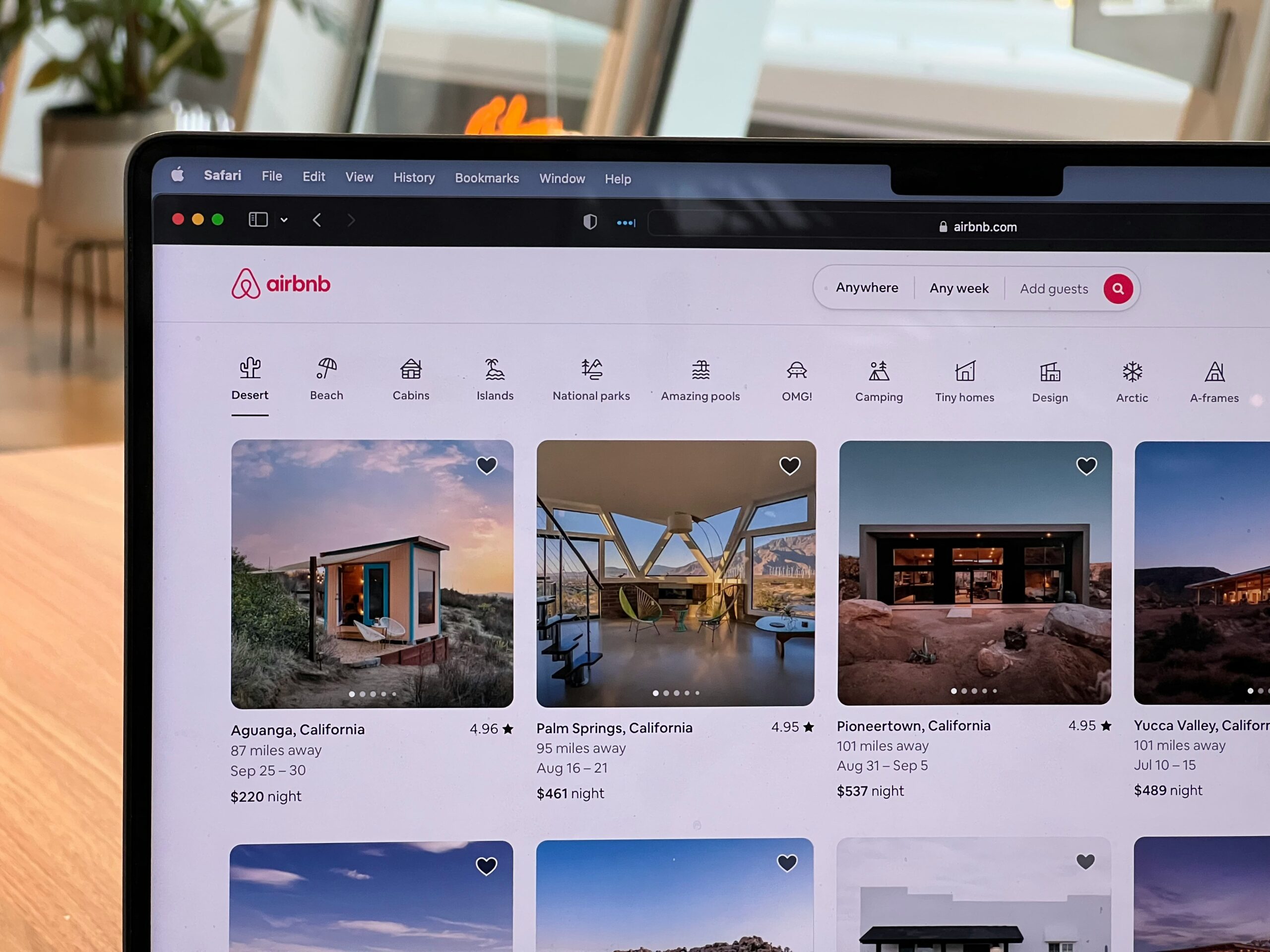

Other campuses argue that the measures have not been adequately funded, with the program being enacted after budgets were already outlined. Principals have provided mixed reports, with some indicating that they’d received free access to the software, while others were informed that the program would need to be paid for out of the school’s budget.

Officials Measuring Sprint Compliance

District officials have indicated that they will review and measure compliance with the program. The preparatory software produces automated reports and metrics that identify time spent using the digital platform, causing some frustration over the micromanagement of classroom instruction. Education Department spokesperson Nicole Brownstein has attempted to address concerns, emphasizing that school leadership may implement alternative strategies instead of digital platforms. While only time will tell if the sprint paid off, educators and district officials have reiterated their commitment to student success.